There isn’t sufficient space to relate more than the barest bones of the saga. Nevertheless, its central figures will surface as regularly as rocks in the stream in an eventual full-scale memoir of my peculiar career – partly because there are still people around today who’ll tell you that (Alan) Clayson and the Argonauts was the greatest group ever formed. Indeed, under certain conditions, I think so myself, but then I was its Marat, its Danton, its Robespierre, its Mirabeau and its Bonaparte. Certainly, there’d never been a time or a situation – or a musical entity – like it.

Clayson and belong to an era nearly as bygone as that bracketed by Hitler’s downfall and “Rock Around The Clock”. We left the runway in 1976 after John Tobler wrote a glowing New Musical Express report on our set when we semi – gatecrashed a bill of pre-punk fare at Guildford Civic Hall. This was only a fortnight after we’d been hustled out of a palais in Reading at gunpoint. The promoter found our show so “rubbish” that he felt entitled not to pay us. On this threshold of eminence too, one key member was gaoled for fifteen months, and two others quit, one of them fated to co-produce Hilda Baker and Arthur Ballard’s chartbusting duet of “You’re The One That I Want”.

Generally, however, the wheels of the universe were rolling in our direction as the watershed year of 1977 loomed. Suddenly, there seemed to be some kind of future with no more hint of tragedy or farce. A few important media and music industry folk started flocking round like friendly if over-attentive wolfhounds, most conspicuously, Ron Watts, a godfather of punk, who had helped Malcolm McLaren launch The Sex Pistols. Thanks to Ron, we made a London debut at the 100 Club (with The Jam, both of us warming up for something called Stripjack) on 9 January 1977. Next up was a full-page Melody Maker Spread, courtesy of its enthralled future editor, Allan Jones. Crucially, I was being spoken of and written about in the same sentences as Wreckless Eric, John Otway, Tom Robinson and Elvis Costello.

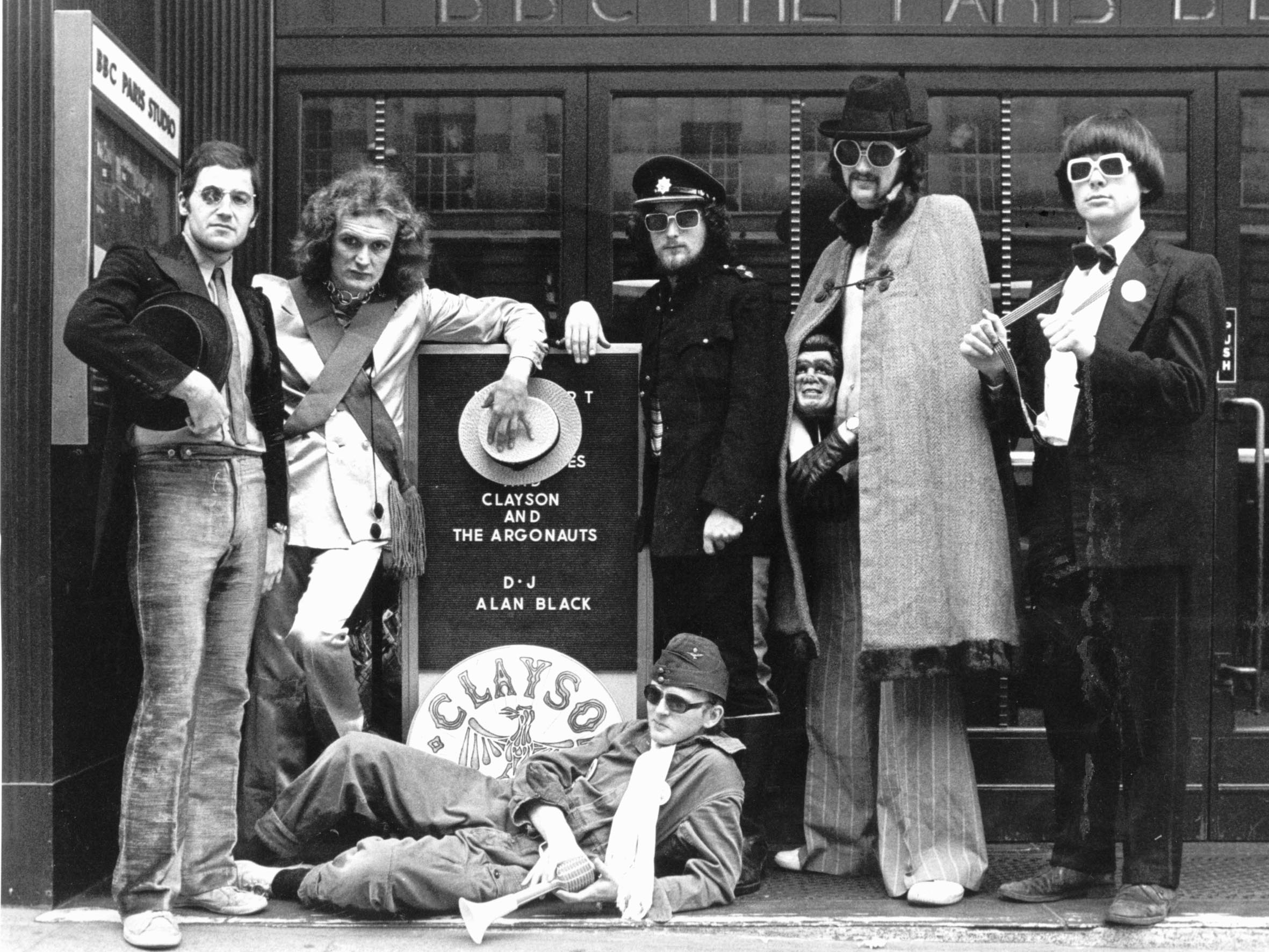

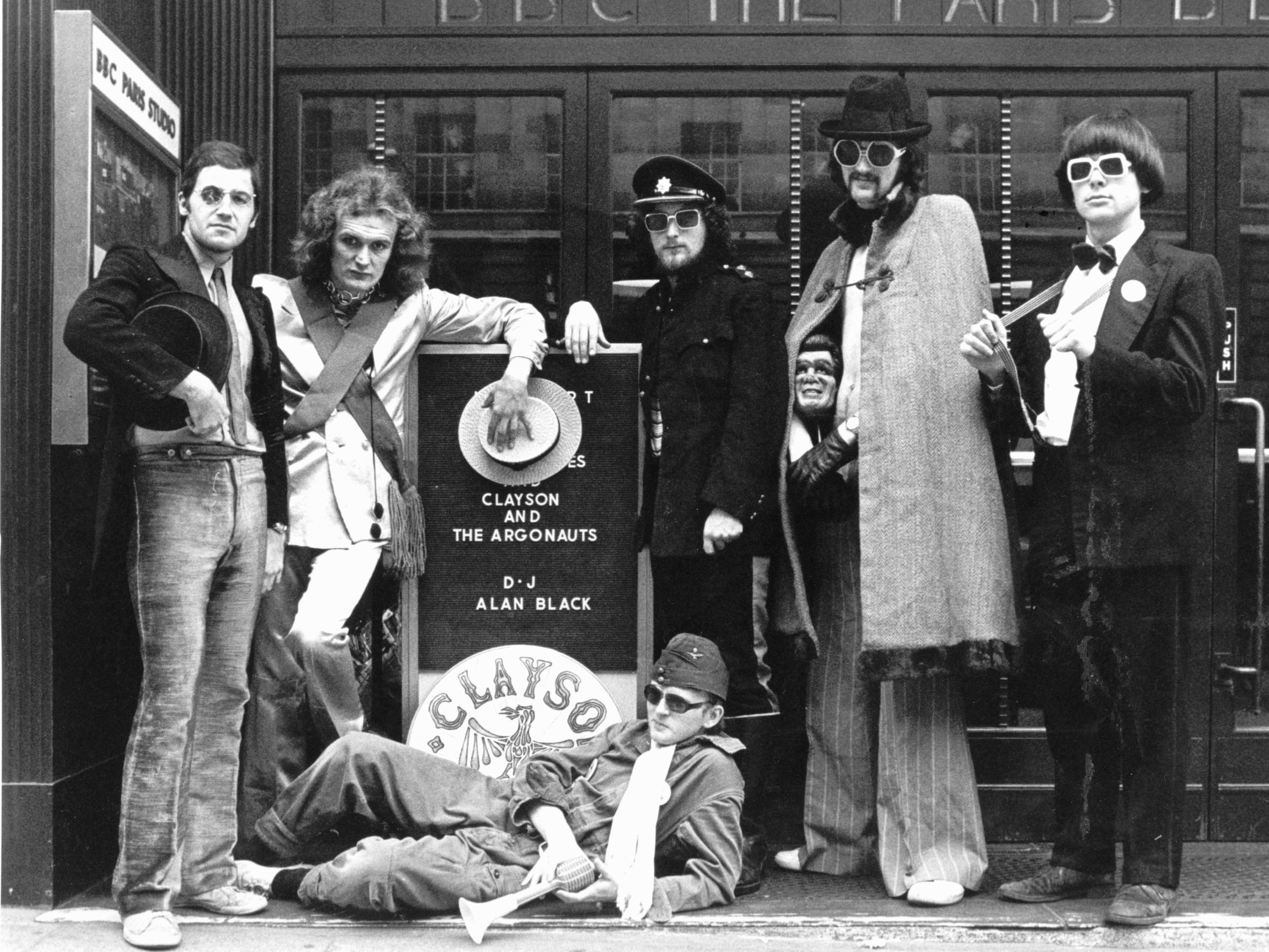

So began three years of expecting to be on Top Of The Pops next week. An almost overwhelming sweep of events embraced more dates than could possibly be kept; a BBC Radio One In Concert (which turned up on a 2001 Clayson bootleg, Ghostly Talking Heads), and headlining at venues such as the Marquee, back at the 100 Club, Amsterdam’s Melkweg and any number of university hops, among them Queen’s College Belfast at the height of the Troubles, where an ecstatic audience was still demanding more after no less

than six encores. In parenthesis, what became The Eurythmics supported us at some college function in the Midlands.

Delivering “more than a performance, an experience” (Sounds), Clayson and the Argonauts were, therefore, a very “happening” group, judging too by the clusters chattering excitedly as they spilled out onto the pavements after a sweatbath with us inside, say, Hugh Wycombe’s Nag’s Head, Eric’s in Liverpool, West London’s Nashville Rooms, the Penthouse in Scarborough or the Exit in

Rotterdam, always one week after Wreckless Eric and one week before The Adverts. En route, we were catalysts of the wreckage of a Luton auditorium; a near-lynching at Barbarella’s in Birmingham; fisticuffs and a consequent car chase following a midnight matinee in Canning Town; a season in a red-light district sur le continent (our “Hamburg” period); a woman clambering on stage to tear off all her clothes at Islington’s celebrated Hope-and-Anchor, and a bloke doing the same during almost-but-not-quite a riot at the Granary in Bristol.

Soon, we were past resistance to the circumstances that had made it impossible to go back then to anyone’s old routine of get up-get to work-get home-get to bed groundhog days that once passed for a life. If the van had drawn up outside a ballroom on Pluto, it mightn’t have seemed all that odd.

Yet fast must come the hour when fades the fairest flower. Furthermore, the underside of our marvellous achievements was that, though I was “in a premier position on rock’s lunatic fringe” (Melody Maker again), I was running a provincial outfit most of the time from a telephone kiosk down the road. All I could promise an Argonauts, fished principally from the same pool of local musicians, was an even more glorious tomorrow.

When it didn’t dawn, our van mutated into a travelling asylum as ears strained to catch murmured conspiracy. A stoic cynicism would sour to cliff-hanging silences, sullen exchanges and the drip-drip of those antagonisms, discords and intrigues that make pop groups what they are. As we lurched from gig to gig, a rueful but light-hearted mood might persist for several miles before a tacit implication in an apparently innocuous remark could spark off a slanging match that would continue on arrival in another strange city, another distant soundcheck, another affirmation of a ramshackle grandeur. Back home, loved ones would wonder in that ancient night until headlamps signalled one more deliverance from the treadmill of the road. Yet there were still moments when…

That there was something not so much rotten but smelling funny in the state of Clayson and the Argonauts became evident firstly when “The Taster”, a godawful one-shot single, was issued on Virgin Records against my better judgement, and damaging to both my confidence and credibility as a composer. Coupled with “Landwaster”, an excerpt from a then-unreleased in-concert LP,

it was a “turntable hit” (e.g. Number Three in Time Out, the London events guide’s chart). Moreover, so I understood later, “Landwaster” entered Belgium’s Top Twenty fleetingly after a pirate radio presenter began spinning it by mistake instead of the A-side.

This 45 was also a prelude to a voyage to a lower circle of hell for me and an Argonauts in gradually more constant flux. Nevertheless, there was always sufficient to feed hope, and I’d been famous enough to want to battle hard against being consigned back to the oblivion from whence I’d come.

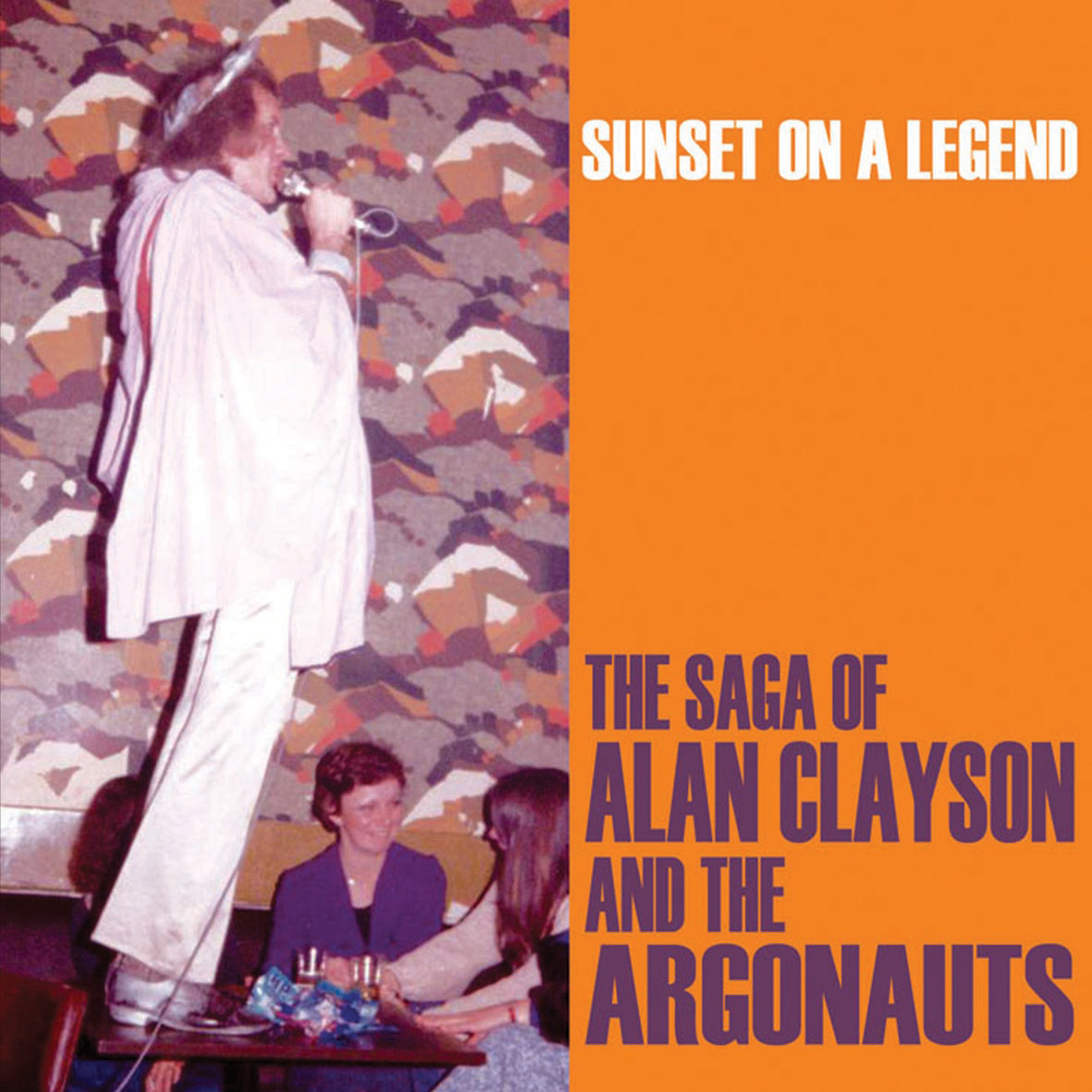

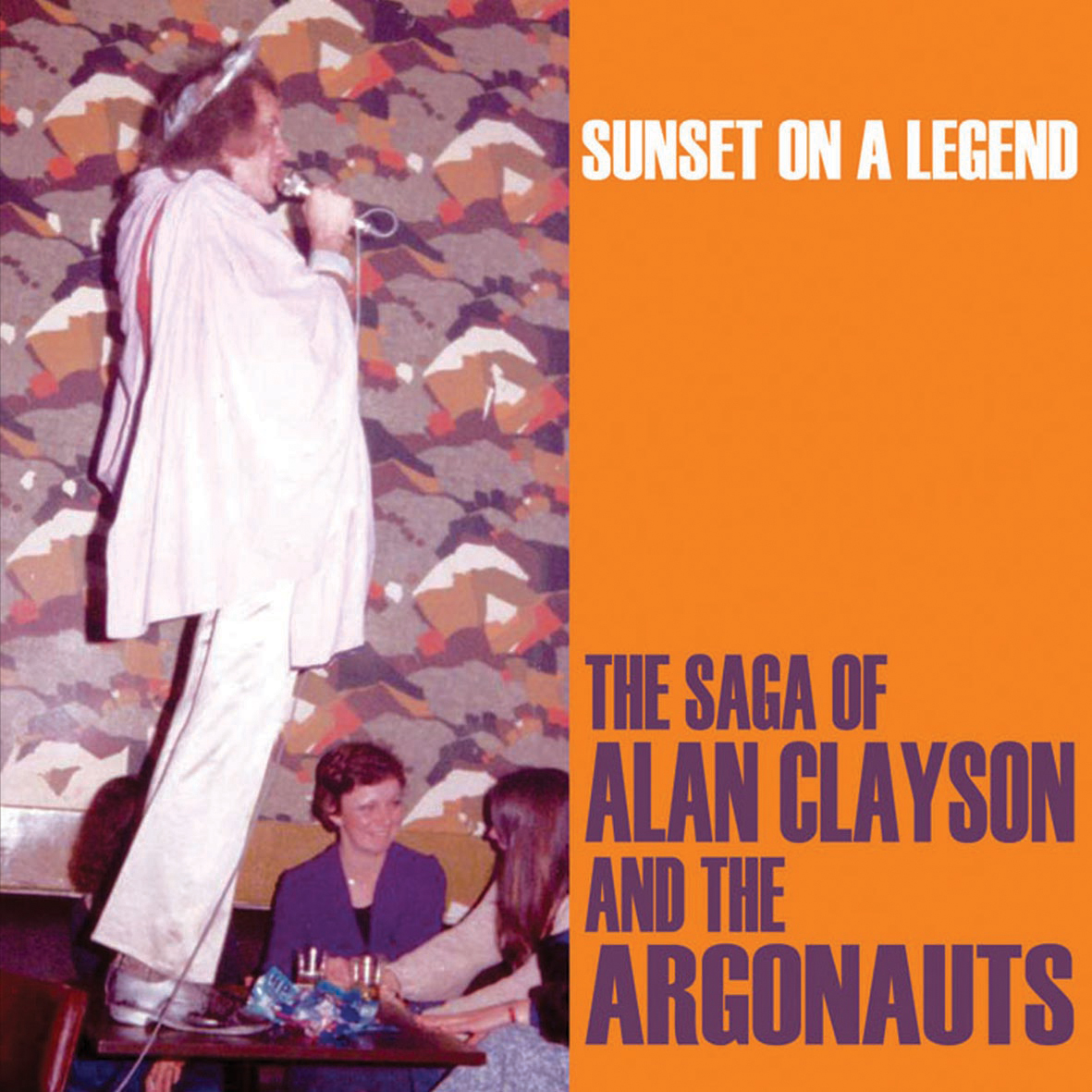

In our decline, an Exeter-based independent label put out a rather eschatologically-titled EP, Last Respects, and an album, What A Difference A Decade Made, was a critical cause célebre, earning rave reviews in both Folk Roots (!) and The Observer.

However, to quote from Tony Hancock’s suicide note, “things seemed to go wrong too many times”. The morning after we played to a crowd of twelve back at the Nag’s Head, I received an agitated call from our road manager to say that, while he was loading up, £500-worth of borrowed microphones had been stolen.

After just over a decade as a working band, Clayson and the Argonauts, our very name now a millstone round our necks, made a final public appearance on 20th January 1986. By then, we were like a soldier that had been fatally wounded, but kept fighting, not knowing how severe the injury was. To all intents and purposes, we’d been over for ages, a faded memory, a tattered

newspaper cutting. Thus we scattered like vermin disturbed in a granary. All that was left – until now – was the sound of our aural junk-sculptures as a spooky drift from the shadows in some lonely back-of-beyond dance hall, maybe one refurbishment away from demolition…

Alan Clayson